Born on May 12, 1820 to wealthy English parents, Florence Nightingale was named after the Italian city in which she was born—Florence, Italy—just like her sister Parthenope who had been born in Naples and was given the Greek name for the ancient city.

When they returned to England, the Nightingale family divided their time between their two homes: Lea Hurst in Derbyshire for the summer and Embley in Hampshire for the winter.

Who Was Florence Nightingale?

Although many Victorian women did not attend universities, pursue professional careers, or receive an education, Florence’s father William believed that his daughters should have the opportunity to get an education. Thus, he decided to teach his daughters a variety of subjects, including Italian, Latin, Greek, history, and mathematics. Florence, in particular, excelled academically, and she received superb preparation in mathematics from her father and her aunt. It is due in part to Florence’s education as a child that her two greatest life achievements—pioneering the field of nursing and reforming hospitals—were possible.

As Florence received her education from a young age, she also was very active in ministering to the ill and poor people in the village near her family’s estate. By the time she reached the age of 16, she believed that nursing was her calling and divine purpose. At first, her family did not take too kindly to this idea.

But Florence insisted. She turned down a marriage proposal and enrolled as a nursing student at the Lutheran Hospital of Pastor Fliedner in Kaiserwerth, Germany in 1844.

Florence Nightingale and the Crimean War

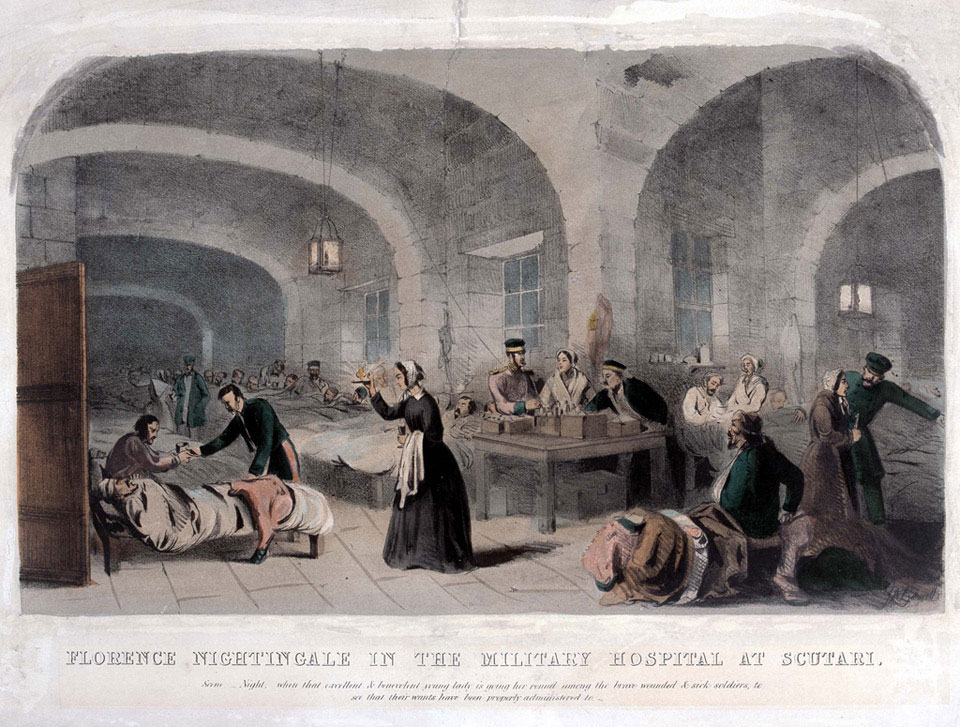

Florence Nightingale became a common household name due to her part in the Crimean War, which lasted from 1854 to 1856. In 1853, Florence had returned to London from Germany and began serving as an unpaid superintendent of an organization for gentlewomen suffering from illness and did so for a year. When the war broke out in 1854, Sidney Herbert, the Secretary of War, recruited Florence and 38 nurses to serve in Scutari during the Crimean War.

Florence and the nurses left London on October 21, 1854, crossing the English Channel, traveling through France to Marseilles, and sailing on to Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul) before arriving on November 3, 1854. Scutari was located near Constantinople, and the conditions were abysmal. The hospital was replete with vermin and lacked even basic equipment and provisions.

Moreover, the medical staff could not keep up with the substantial number of soldiers who were being shipped from across the Black Sea away from the fighting in Crimea. Even worse, more patients were dying from disease and infection than from battle wounds.

Florence Nightingale in Florence

Florence and her nurses got right to work. They turned the hospital into a significantly more healthy environment by washing the linens and clothes, improving the medical and sanitary arrangements, writing home on behalf of the soldiers, and introducing reading rooms. Within six months, the death rate of the patients fell from 40 percent to a mere 2 percent.

It was here at Scutari that Florence would acquire the nickname of “the Lady with the Lamp.” According to the Times, Florence would walk among the beds at night, checking on the wounded men with a light in her hand. This image—in a similar way to the flag-raising at Iwo Jima—captivated the public, and she became a celebrity with her own “cult following.”

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow was one of many to admire Florence and immortalized her in his poem Santa Filomena:

Whene’er is spoken a noble thought Our hearts, in glad surprise, To higher levels rise. The tidal wave of deeper souls Into our inmost being rolls, And lifts us unawares Out of all meaner cares. Honor to those whose words or deeds Thus help us in our daily needs, And by their overflow Raise us from what is low! Thus thought I, as by night I read Of all the great army of the dead, The trenches cold and damp, The starved and frozen camp, — The wounded from the battle-plain In dreary hospitals of pain, The cheerless corridors, The cold and stony floors. Lo! in that house of misery A lady with a lamp I see Pass through the glimmering of gloom And flit from room to room. And slow, as in a dream of bliss, The speechless sufferer turns to kiss Her shadow, as it falls Upon the darkening walls. As if a door in heaven should be Opened, and then closed suddenly, The vision came and went, The light shone and was spent. On England’s annals, through the long Hereafter of her speech and song, That light its rays shall cast From portals of the past. A lady with a lamp shall stand In the great history of the land, A noble type of good, Heroic womanhood. Nor even shall be wanting here The palm, the lily, and the spear, The symbols that of yore Saint Filomena bore.

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

After several months of working at the hospital in Scutari, Florence desired to witness the conditions of the army at Balaklava herself and left on May 2, 1855. In just a few days of arriving in the harbor, she was struck with “Crimean fever,” and it was feared that Florence would die. By the end of the month, however, Lord Raglan telegraphed London that she was out of danger. Nonetheless, her complete recovery was slow due in part to her demanding schedule as a nurse.

Florence’s experiences in the Crimean War completely changed her, and when she returned to England in August 1856, she began to campaign for the reform of nursing and the sanitation of hospitals. Within three years, the Nightingale Fund had reached over £40,000, which Florence used to establish the Nightingale Training School at St. Thomas’ Hospital on July 9, 1860. After nurses received their training, they were sent to hospitals across Britain to introduce Florence’s ideas.

Florence Nightingale's Books

Around this time, Florence also published two books, Notes on Hospital and Notes on Nursing, both published in 1859. These books, in addition to about 200 other books, pamphlets, and reports on hospital, sanitation, and other health-related issues, would lay the foundations for modern nursing.

Florence lived until the age of 90, dying on August 13, 1910. Even though she had the opportunity to buried in Westminster Abbey, her relatives declined the offer, and she was instead buried at St. Margaret Church in East Wellow near her parents’ home.

Florence’s work and achievement cannot be understated. She turned nursing into a respectable profession for women. Previously with the exception of nuns, most women who worked as nurses were working-class and often poorly trained and disciplined. Florence was determined to educate women in the field of nursing and turn it into a respectable occupation. Due in large part to her work in Crimea, Florence helped to transform the public image of nursing.

The Legacy of Florence Nightingale

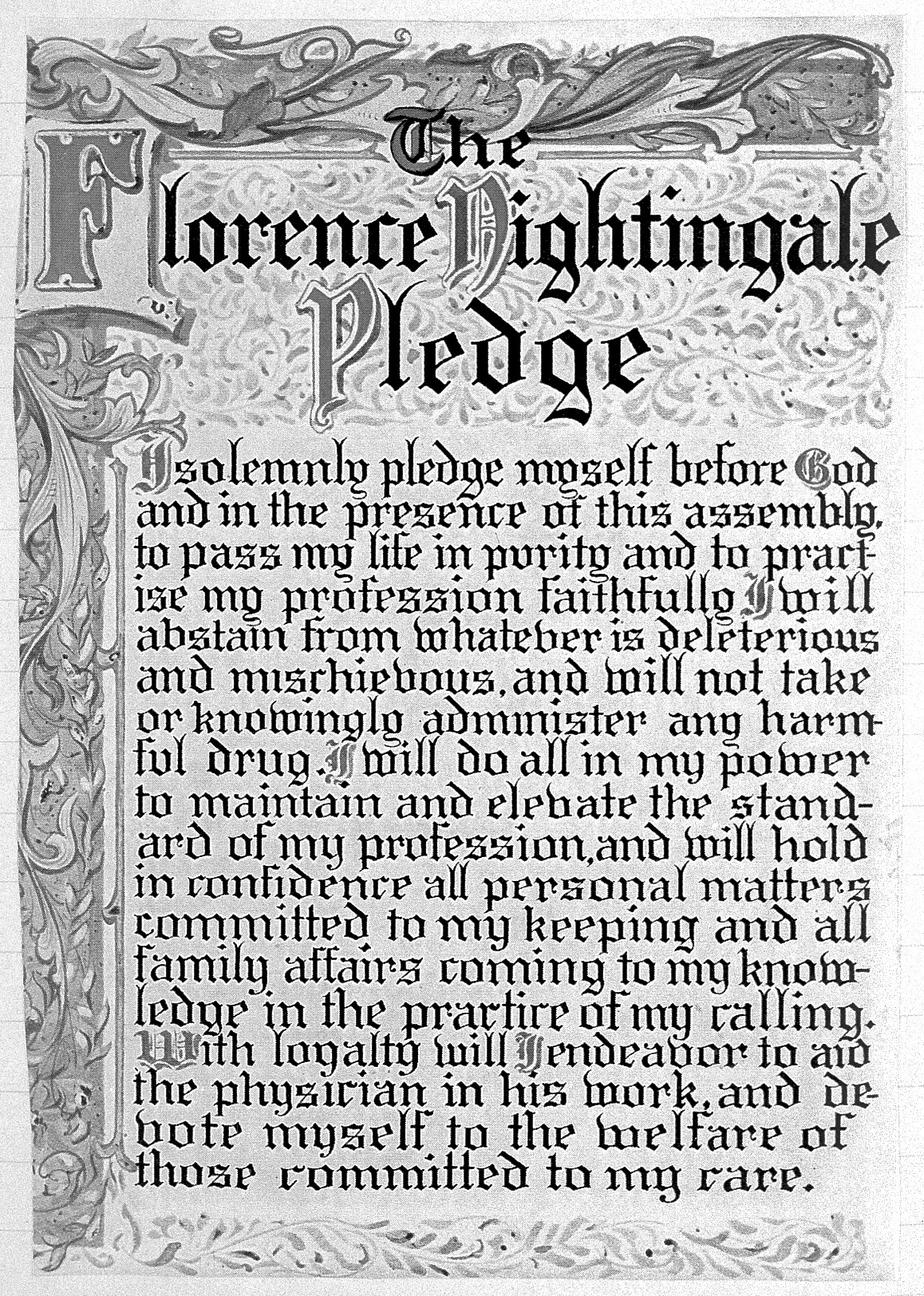

Even today, Florence continues to be recognized for her pioneering work. New nurses take the Nightingale Pledge, and the Florence Nightingale Medal, issued by the International Committee of the Red Cross beginning in 1912, is the highest international award that a nurse can achieve.

Like the woman named in honor, the Florence Nightingale Medal is awarded to nurses or nursing aides who exhibit “exceptional courage and devotion to the wounded, sick or disabled or to civilian victims of a conflict or disaster” or “exemplary services or a creative and pioneering spirit in the areas of public health or nursing education.” In addition, International Nurses Day has been celebrated on her birthday (May 12) each year since 1965.

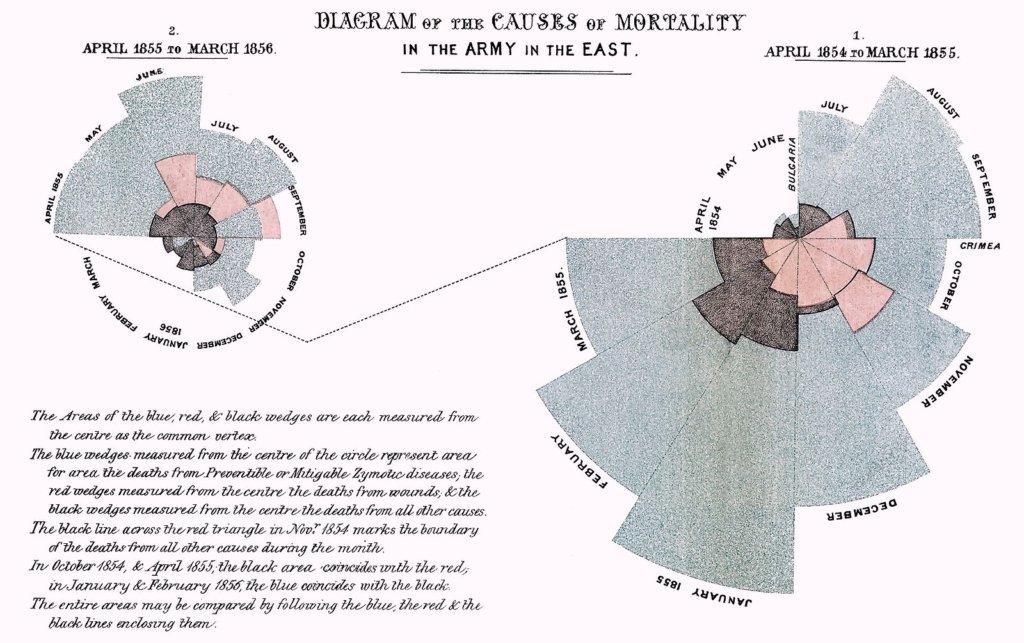

Less well known are Florence’s mathematical achievements. However, her reforms in hospital sanitation methods were due to her use of new techniques in statistical analysis. Florence developed a “polar-area diagram” to depict the needless deaths that had been caused by unsanitary conditions. In this way, Florence was innovative in collection, graphical display, interpretation, and tabulation of descriptive statistics.

Even today, Florence continues to be recognized for her pioneering work. New nurses take the Nightingale Pledge, and the Florence Nightingale Medal, issued by the International Committee of the Red Cross beginning in 1912, is the highest international award that a nurse can achieve.

Like the woman named in honor, the Florence Nightingale Medal is awarded to nurses or nursing aides who exhibit “exceptional courage and devotion to the wounded, sick or disabled or to civilian victims of a conflict or disaster” or “exemplary services or a creative and pioneering spirit in the areas of public health or nursing education.” In addition, International Nurses Day has been celebrated on her birthday (May 12) each year since 1965.

Less well known are Florence’s mathematical achievements. However, her reforms in hospital sanitation methods were due to her use of new techniques in statistical analysis. Florence developed a “polar-area diagram” to depict the needless deaths that had been caused by unsanitary conditions. In this way, Florence was innovative in collection, graphical display, interpretation, and tabulation of descriptive statistics.

Florence even received an award from Queen Victoria herself: a jeweled brooch designed by Victoria’s husband, Prince Albert, with the dedication: “To Miss Florence Nightingale, as a mark of esteem and gratitude for her devotion towards the Queen’s brave soldiers.”

Sources:

- https://library.uab.edu/locations/reynolds/collections/florence-nightingale/life

- https://www.nam.ac.uk/explore/florence-nightingale-lady-lamp

- https://www.agnesscott.edu/lriddle/women/nitegale.htm

- https://www.history.com/topics/womens-history/florence-nightingale-1

Guest Contributor: Rachel Basinger is a former history teacher turned freelance writer and editor. She loves studying military history, especially the World Wars, and of course military medals. She has authored three history books for young adults and transcribed interviews of World War II veterans. In her free time, Rachel is a voracious reader and is a runner who completed her first half marathon in May 2019.